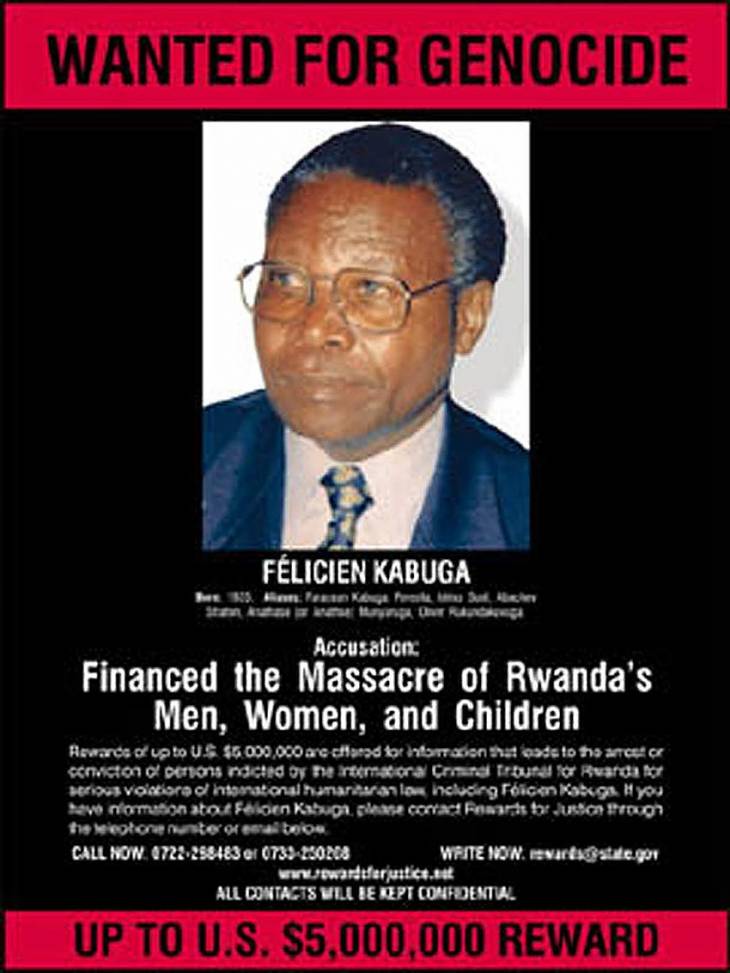

Félicien Kabuga, the great paymaster of the Rwandan regime in the early 1990s, accused of genocide, was arrested on 16 May in France. For 23 years, he had escaped international justice. His surprise arrest raises many questions. Including that of a “reopening” of the UN Tribunal for Rwanda. A long-read by JusticeInfo.net, Fondation Hirondelle’s news website on international justice.

It is arguably the most remarkable flight of an accused person before contemporary international criminal tribunals. For nearly a quarter of a century, five international prosecutors have succeeded one another, thinking, fighting or dreaming about the arrest of Félicien Kabuga. This son of modest peasants, who started out from nothing to build Rwanda’s biggest fortune in the early 1990s, has been taunting officials at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) since 1997. Relying on his connections and wealth, moving around under false identities, residing in different countries in Africa and Europe, he became known as “the elusive one” among Rwandans—until the early morning of 16 May 2020, when the French police picked him up in an apartment in a Parisian suburb.

Aged 84 and in an apparently fragile state of physical health, Kabuga was arrested in Asnières-sur-Seine, according to a joint statement by the Paris Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Central Office for the Fight against Crimes against Humanity (OCLCH). He has since been held in a prison in the French capital.

The operation came as a huge surprise. Nobody really expected that this former paymaster of a Rwandan regime that had presided over the genocide of the Tutsis between April and July 1994 would be arrested.

The mystery of Kabuga’s arrival in France

This major arrest may first shed some light on how Kabuga was able to evade his hunters for so long. It is established that Kabuga went to Switzerland in the aftermath of the genocide, quickly left that country in 1995, and notoriously settled in Nairobi, the Kenyan capital. In 1996, he resided there openly, confident of the protection then afforded by the Kenyan authorities to many former Rwandan leaders now accused of genocide. In July 1997, the ICTR organized its first major dragnet in Kenya. Kabuga was one of the targets of the operation. He narrowly escaped. Since then, he has been “the elusive one”. Over the years and with the authorities’ failures to apprehend him, he became a “cold case”, one that officials from the ICTR, and the UN body that succeeded it—the International Residual Mechanism for International Tribunals (IRMCT)—regularly brandish. However, without much hope of his capture, he no longer represented a priority for the national police forces on which the UN tribunal depends in its hunt.

Many questions remain about the formidable Kabuga escapade. The most burning one is: how and when did he enter French territory? “We don’t know how long he’s been in France,” OCLCH head Eric Emeraux told Justice Info a few hours after he and his men arrested the Rwandan. “Our mission was to find him, execute the arrest warrant and hand him over to the authorities of the Mechanism. We are not in charge of the investigation. My personal intuition is that he has been there for a while,” added the French gendarmerie colonel. Olivier Olsen, the managing agent of the building where the fugitive resided, told AFP that the “old man, very discreet”, “had been living there for three or four years”.

Trapped by modern technology

According to Emeraux, the hunt for Kabuga was relaunched a year ago at a meeting in The Hague under the aegis of the Mechanism. Family members of the runaway were then placed under surveillance by the Belgian, British and French police, depending on where they resided. It is this exchange of information between European countries that made it possible, explains Emeraux, to trace the Rwandan’s whereabouts. Two months ago, before the French population was subjected to strict confinement in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, a new meeting was held, under the aegis of Europol and with the cooperation of the Mechanism. “There, we were aware that there was a good chance that he was, in fact, in Europe,” says Emeraux.

The attention of the French services was focused on an apartment that Kabuga’s family members often visited. Electronic surveillance allowed them to see that, over 365 days, one of Kabuga’s children (he has had eleven) was always present in the apartment. Even though the authorities were not certain that the fugitive was there, “[w]e had good reason and a lot of evidence to think he was [inside], but until we pushed open the door to his room, we weren’t sure. We would have been sure if we’d seen him come out. He was very discreet. And he was confined. He was living under a false identity with a passport from an African country I’d rather not name. He had 28 aliases anyway, in 26 years,” says Emeraux.

When the police finally entered the apartment, indeed the old man was there, with one of his children. “Nobody sold him. No one will get the 5 million dollar reward” that the American government has been promising for 20 years, adds Emeraux. In the end, once the cold case was brought to light, Kabuga was apprehended quickly with technological investigative methods that are routine today.

The Rwandan government welcomes the arrest

It is difficult, at this stage, to assess the impact of the stormy political relationship between France and Rwanda on the outcome of the Kabuga case. Since 1994, the French authorities have been accused by Rwanda of sheltering or protecting those allegedly responsible for the genocide. But after Emmanuel Macron came to power in France three years ago the relationship between the two countries clearly improved. The capture of Kabuga obviously fits into this new period of pragmatic appeasement, even if it may not be directly linked to it.

In Kigali, the tone is suddenly no longer one of recriminations against France. “We welcome Kabuga’s arrest and the fact that he will be brought to justice. It’s an act that reflects good relations and collaboration. It should make the other fugitives understand that they will eventually be arrested,” said Rwanda’s Justice Minister Johnston Busingye in an interview with Justice Info. Earlier, on government television, the minister hailed “another level of cooperation [with France], a commitment to justice, a new momentum, a message to the world, a new wake-up call.”

There was a similar sense of satisfaction among genocide survivors, although they would have liked to see Kabuga tried in Rwanda. “We are grateful to all those who contributed [to his arrest], such as the French judiciary and the IRMCT, which has never ceased to hunt him down. The fact that he has been arrested and will be brought to justice is a good thing, but for us it would be justice twice over if Kabuga were extradited and tried here at home. It would be a good lesson for the other genocidaires, especially those who killed with the weapons he made available to them, those he personally incited to commit the crime,” Naphtal Ahishakiye, secretary general of Ibuka (“remember” in Kinyarwanda), the main survivors’ organization, told Justice Info.

Recommended reading

Rwanda: The most judged genocide in history

A strategic success for Prosecutor Brammertz

However, such a prospect is unlikely. When the ICTR officially closed its doors, it decided to transfer the files of several fugitives to the Rwandan justice system. But it retained jurisdiction over three prominent suspects, the former head of the presidential guard, Protais Mpiranya, former Defence minister Augustin Bizimana, and Félicien Kabuga. (Mpiranya and Bizimana were never arrested and were reported dead many years ago without official confirmation.)

It is therefore to the “Mechanism”, the IRMCT, that Kabuga must be surrendered for trial. As a result, one of the great beneficiaries of Kabuga’s arrest is undoubtedly the IRMCT prosecutor, the Belgian Serge Brammertz. He can claim to have succeeded where all his predecessors have failed. Appointed to the Mechanism in 2016, Brammertz is among the leading candidates for the post of prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, which is due to be filled in December. There is no doubt that this success serves his candidacy. “For international justice, Kabuga’s arrest demonstrates that we can succeed when we have the international community’s support,” Brammertz said in a statement, thanking no less than 10 countries for their “essential contribution”.

But there are great unknowns in the proceedings that lie ahead. First, it was announced that Kabuga would be transferred to The Hague. But the Mechanism has a large and expensive headquarters in Arusha, Tanzania, where Kabuga is supposed to be tried. For the IRMCT and its UN staff, the arrival of Kabuga sounds both like the end of a quiet and undemanding work routine, and the promise of new hires and an increased budget for several years, if the health of the accused permits. How long will this trial take, given the difficulty of such an unprecedented “restart” of an international court and the proverbial slowness of its proceedings? And at what cost?

Seven counts

The indictment against Kabuga, on the basis of which the French police acted, originated in 1997. It has undergone several amendments over years of investigations. The last amended indictment dates from 14 April 2011. Kabuga is charged with seven counts: genocide, complicity in genocide, direct and public incitement to commit genocide, attempt to commit genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide, and the crimes against humanity of persecution and extermination.

It is thus summarized by the IRMCT in the information sheet published on its website: “According to the indictment, … Félicien Kabuga, together with certain other persons, agreed to plan, create and fund a militant group known as Kabuga’s interahamwe in Kimironko sector, Kigali, the purpose of which was to further ethnic hatred between the Hutus and Tutsis in Kimironko sector with the goal of committing genocide against persons identified as Tutsis.” Kabuga is accused of having “planned or intended the killings of persons identified as Tutsis by his Interahamwe, or he knew that they were committing these killings between April and July 1994 in different locations”. The indictment also mentions that he did not take any measures to prevent these killings although he had the power to use his influence and financial means to do so. It further “alleges that the radio station RTLM, founded by Kabuga, directly and publicly incited the commission of genocide through broadcasts that expressly identified persons as Tutsis, provided their locations, described them as the enemy, and called for their elimination.”

From 2011 to 2012, the ICTR collected “special statements” in the case of the former businessman. As part of this procedure to preserve evidence, the Prosecutor and the court-appointed Defence counsel interviewed witnesses. Their statements may be used in the upcoming trial.

What to expect from a trial?

There is doubt, however, that the future trial will shed more light on the history of the genocide in Rwanda. For French sociologist André Guichaoua, a specialist on Rwanda and expert witness for the prosecutor in most ICTR cases, only a guilty plea procedure could both benefit the elderly accused and shed light on dark sides of the genocide. “Justice is also, and above all, about telling the truth. In this case, while lengthy proceedings are to be expected and it is doubtful that there is any other outcome than life imprisonment, that is the only issue at stake in the old Félicien Kabuga case,” he said. “All the parties have an interest in giving themselves the means to achieve this through demanding confrontations, likely to erase the criticisms and even contempt that many States and individuals have for the ICTR. With the arrest of Félicien Kabuga, this objective must take precedence. In this case, the guilty plea procedure would save the institution”, concludes the expert.

Such a prospect is highly uncertain. But it would then make Kabuga go down in legal history for something other than his spectacular and long escape.

Recommended reading

Rwanda, 25 years after the genocide

WHY KABUGA IS IMPORTANT

Kabuga is a central figure in the history of the genocide for several reasons. He was behind the creation of several key organisations in the execution of the genocide, including the Interahamwe Youth, which was transformed into an armed militia and became the spearhead of the massacres from April 1994 onwards, and the Radio-Télévision libre des mille collines (RTLM), a media outlet which incited hatred of Tutsis and was guilty of direct calls for murder during the genocide. Kabuga was president of the RTLM Initiative Committee. During the 1994 massacres and civil war, Kabuga also became president of the Provisional Committee of the National Defence Fund (FDN), in support of the genocidal government.

Kabuga is also important because he belonged to the presidential family, that of Juvénal Habyarimana, who was in power from 1973 until his assassination on 6 April 1994, the event that triggered the genocide. Through Kabuga, international justice can hope to repair one of its great failures: to establish the responsibility of the members of this family in the planning and execution of the genocide. The ICTR has never succeeded in building a solid and credible criminal case against Agathe Kanziga, President Habyarimana’s widow. It has dramatically failed to obtain the conviction of Protais Zigiranyirazo, better known as “Mr. Z”, Agathe’s brother, who was suspected of being behind death squads in the 1990s and against whom several remarkable testimonies allege his direct and essential role in the order given for the first assassinations at the dawn of 7 April 1994. “Mr. Z” was however acquitted on appeal by the UN court. For the Rwandan victims and many historians, this is perhaps the court’s greatest mistake. Through the marriage of their children, Kabuga is part of the Habyarimana family and its first circle. He is thus the last chance to obtain a condemnation, symbolically at least, of the presidential clan of that time.

Finally, Kabuga is a financier. His alleged crime is to have been the one who financed the genocide. Yet all contemporary international tribunals for mass crimes have failed to target the money men behind the crime. As such, Kabuga represents a final opportunity to make up for this chronic deficit in prosecutions before international courts.