We have just celebrated World Press Freedom Day on Monday 3 May. The theme chosen by UNESCO this year was “information as a public good”. The vital and public interest role of access to quality information has been at the heart of Fondation Hirondelle’s work for over 25 years. It is this experience that we draw on today to explain our approach to responding to disinformation, a plague that undermines all societies around the world.

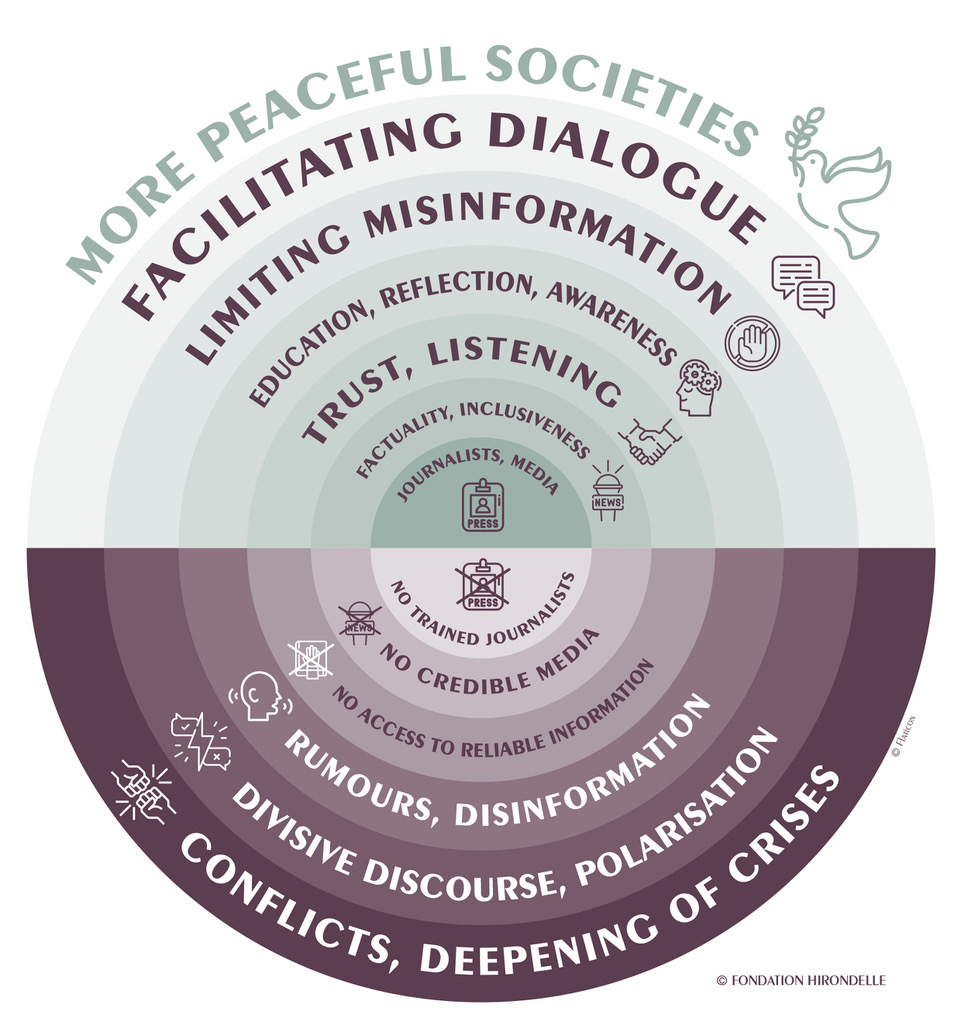

Fondation Hirondelle’s approach to disinformation centres on the fundamental principles of journalism and on the lessons learned from over 25 years of applying these principles in highly fragile contexts, where access to reliable information for the majority is not a given, and where rumours, hate speech and propaganda undermine peace building and development.

Our response to disinformation is based on two complementary axes: sticking to the facts and building trust.

STICKING TO THE FACTS

- INDEPENDENCE: Editorial independence is essential for ensuring the fairest possible treatment of facts. Whether the owner of a media organisation is the state, a business-owner, or an association, it is important to guarantee the independence of the work of journalists. This independence must be asserted and protected by guidelines, codes, charters, and by the daily application of good practice to avoid interference between the management of the media and the editorial staff. Read, for example, the charter for radio stations in Mali[1], adopted in February 2021 in Bamako by the High Authority for Communication and the Union of Free Radios and Televisions of Mali, and inspired by Studio Tamani, Fondation Hirondelle’s radio programme in Mali.

- RELIABILITY: The production of factual, reliable information depends on access to legitimate, verified sources. This access is often complicated or even prevented by governments, administrations or companies, especially regarding sensitive subjects, in conflict situations or under undemocratic regimes. Knowing how to identify reliable sources is all the more crucial for journalists in these situations. Watch our video “masterclass in journalism“[2], on the treatment of sources, with Guillaume Daudin, journalist at Agence France Presse.

- REACTIVITY: Stories must be reported on when and where they are happening. Journalists must be able to operate in the field, reaching the scene quickly when something happens, in order to meet the information needs of the population, and to limit the space for rumours – in the absence of factual, verified and reliable information, rumours quickly fill the void[3].

- PROPORTION: An on-the-ground approach to journalism helps ensure that news coverage addresses the real concerns of audiences and treats issues in a way that is proportionate to people’s priorities and everyday realities, thus avoiding the imposition of outside agendas. Misinformation must also be treated with a sense of proportion: placing too much emphasis on false rumours can contribute to their spread.

- CLARITY: It is critical to acknowledge the distinction between what is fact and what is opinion. This is what enables a news organisation to retain credibility in the eyes of the public. The role of a journalist is not to share their personal views, but to deal with facts and explain them as objectively and clearly as possible. Opinions of interlocutors should be presented as such. The blurring of lines between, on the one hand, factuality (whose sole purpose is to reflect reality as closely as possible by presenting facts) and on the other hand, campaigning, public relations or messaging (whose aim is to persuade) is also counterproductive to efforts to combat disinformation. Media who merge fact-based content with messaging campaigns (institutional, health, commercial, political…), without making a clear distinction between the two, risk undermining trust in their journalistic content.

CONDITIONS: The act of identifying and effectively communicating facts is not a simple task, it is a profession – that of a journalist. This a profession that must be learned. It requires training, technical and financial resources, and time. Journalists who are poorly trained or poorly paid are more likely to deliver a poor handling and reporting of the facts. Such journalists can then become vectors of mis- or disinformation themselves, and lose the public’s trust, at the risk that audiences no longer distinguish between providers of information and providers of disinformation.

To ensure that factual information processed by journalists reaches the public, the public must have access to credible and professional news media. This access must be easy and must be free or low cost, in order to reach the greatest number of people, especially the poorest. Traditional media, such as radio, thus remain effective vectors, alongside or in combination with online and social media broadcasting. These media must have the technical, human and financial means to ensure the production and dissemination of their information.

BUILDING TRUST

- PROXIMITY: Trust is built on relationships of proximity. This is not just about geographical proximity, it is also about speaking to people in their own languages, about addressing issues that concern them directly in a way that is easily understandable to them, via accessible media and in formats that speak to them and engage them. Those media that are close to their audience can serve as catalysts for social empathy, countering the effects of divisive discourses, ‘echo chambers’ and disinformation bubbles that isolate rather than unite people.

- INCLUSIVITY: Those media that offer inclusive and balanced dialogue programmes, bringing together different fields of opinion and components of the society that they address, are more likely to be trusted, because each and every person feels that their voice and needs are being heard and taken into account.

- SINCERITY: Trust requires sincerity: not hiding the things that are wrong, not minimising problems (nor giving them undue importance), daring to take on even the most sensitive subjects, in order to provide an honest treatment of the facts.

- TRANSPARENCY: For the public to embrace fact-based content, the media supplying it must be perceived as credible and impartial. There is no such thing as absolute impartiality or objectivity. It is a question of striving for this with honesty, by telling the public in a clear and transparent way who we are: who owns the media, who finances it, what its editorial line is; and for journalists to explain how they work, who they are, how they process information, and how they strive to remain impartial. See, for example, the normative work of the Journalism Trust Initiative[4].

- LISTENING: In order to build trust with audiences, media organisations need to listen to them: they must consult audiences to understand their needs, priorities, expectations and opinions on their programmes, in order to be able to serve them better. The creation of processes to monitor discussions and discourse online and offline is required to better understand audiences and the disinformation they are confronted with. To do this, media must partner with researchers and experts who can help them develop new monitoring tools to identify the vectors and subjects of disinformation. Read for example the study on the sources and circulation of information in North Kivu, DRC[5], conducted in 2019 by a consortium composed of Fondation Hirondelle, the British think-tank DEMOS, the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative and the Congolese Institute for Research and Development and Strategic Studies.

CONDITIONS: Education about the way information is processed, shared and consumed (referred to as “media literacy”) is also required to help re-establish trust between the media and the public. This does not entail journalists preaching or justifying themselves, but rather giving people the tools to question how and from where they get their information, so that we can all take a step back from our cognitive biases, from the tricks our brains play on us. In order to be credible and to be heard, journalists themselves must know how to question themselves, and sometimes they must share their own doubts – and even their mistakes – with the public. Media literacy programmes can be produced and broadcast by the media themselves and/or in partnerships with universities, researchers and other civil society actors. See for example our series of video masterclasses in journalism.

THE CHALLENGES

- In the global battle for our attention, “fake news”, rumours, divisive messages, and entertaining and banal videos (disinformation often looks entertaining) have a considerable cognitive advantage over factual information, and we must use our ability to reason, think and question. A major challenge for news media worldwide is to capture the public’s attention, competing with the ‘candy’ of simplistic, rewarding, amusing or shocking content that floods our news feeds and web pages[6].

- Rumours have always existed, and they also circulate “offline”, by word of mouth. But the mass of disinformation on social media can cause even greater damage, as it often appears very convincing thanks to the sophisticated means technology employed: Deep-fake videos, highly-convincing fake press releases, conspiracy-theory-based documentaries produced with resources equivalent to those of mainstream television channels… It is sometimes difficult to distinguish “fake news” from real information.

- This battle for the public’s attention also has a financial dimension. The economic model of social media is based on content that is likely to generate a maximum number of “clicks” and easily capture our attention. Gratifying content that traps us in information bubbles (“echo chambers”), and divisive content that makes us react, have a competitive advantage and circulate more widely. Moreover, these digital platforms (such as Google and Facebook) are absorbing advertising revenues, thus depriving the news media of vital sources of income. This is occurring when the business models of news media have already long been in crisis. Economically fragile media, with fewer journalists and less capacity to process information, are less able to respond to disinformation and are more vulnerable to partial interests.

- The monitoring of disinformation is hindered by the reluctance of social network platforms and owners to reveal the workings of their successful algorithms. This monitoring is even more difficult on popular mobile messaging applications, such as WhatsApp, where the spread of disinformation is massive but very difficult to identify at the time, including for ethical reasons of access to private groups (a textbook example of this flood of false information on messaging apps occurred in Brazil during the election of Jair Bolsonaro, and also more recently during numerous elections in Africa, such as in Niger or the Central African Republic at the end of 2020).

- There are many actors involved in the spread of mis- and disinformation: governments, political parties, companies, religious groups, armed groups, associations, media, bloggers, singers, actors, celebrities and ordinary citizens. This is why media literacy efforts should be aimed at all categories of the population, and not only, for example, at young people (a study carried out on the 2016 American election campaign[7] showed that people over 65 years old had shared much more false information than young people under 30).

To governments and development aid donors

- Avoid confusing strategic communication efforts (which may be legitimate, and even in the public interest, for example in the context of the fight against the pandemic) with support for news media. Blurring these lines risks damaging the media’s credibility, undermining audience trust, and thus the impact of the information that media share

- Support local news media, to avoid a ‘vacuum’ of reliable information for the populations that need it most, in environments where access to information is not a given for the majority

- Support the training of journalists so that they are able to provide quality work that ensures greater credibility of information and the ability to debunk rumours

- Support media literacy programmes, so that citizens are equipped with the tools and critical reflexes on the information they receive, are aware of their own cognitive biases and how these can be exploited by (dis)information outlets, and are able to distinguish between information and disinformation

- Support research programmes and monitoring efforts on disinformation and the role of public service media

- Support local institutions to adopt regulatory frameworks that respect media independence and promote access to public information

To policy makers and institutions

- Do not disseminate incorrect or approximate information, as this damages the credibility of your institution and those who relay your official message

- Do not confuse the dissemination of public service messages with the promotion of your policies

- Do not confuse public service media with state media

- Respect the independence of the media, both public and private

- Ensure the adoption/evolution of regulatory frameworks that respect the independence of the media and promote their access to public information

- Ensure access and rapid response to journalists so that they can carry out their work and respond quickly to legitimate public concerns

- Avoid categorising verified information as “false”; avoid discrediting the work of journalists and news medi

To media owners:

- Do not disseminate incorrect/approximate information, it damages the credibility of your media and those who relay your content

- Respect the independence of your editorial teams

- Ensure decent working conditions for your journalists

- Provide regular training for your journalists

To companies and web and social media organisations:

- Work with media and researchers on disinformation monitoring programmes

- Modify your algorithms to promote verified informative content, and to decrease the circulation of “fake news” and disinformation

- Agree to a fairer sharing of advertising revenues with the media for the dissemination of their information

[2] https://www.hirondelle.org/en/masterclasses-the-basics/1283-guillaume-daudin-the-handling-of-sources

[3] This lack of information, which encourages the spread of rumours, is all the more dangerous and damaging in fragile and conflictual contexts. Read Marie-Soleil Frère & Anke Fiedler : Balancing Plausible Lies and False Truths, Perception and evaluation of the local and Global News, Coverage of Conflicts in the DRC, in Romy Fröhlich, (Ed.), Media in war and armed conflict: The dynamics of conflict news production and dissemination (2018) London, New York: Routledge. pp. 271-284

[6] Cf. Gérald Bronner, « Apocalypse cognitive », Presses universitaires de France, 2021