Misa Ramisarivelo is Editor-in-Chief of Studio Sifaka, a radio programme for young people in Madagascar, created by the United Nations in partnership with Fondation Hirondelle. She explains the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on her country, and on the work of journalists.

While the country has not officially experienced any deaths related to the new Coronavirus so far and the number of infected people seems very limited, what are the concrete consequences of the Covid-19 crisis for the population in Madagascar, beyond the health aspect?

Indeed, Madagascar is “spared” by this epidemic compared to other countries despite the precarious living conditions of the population in general and the problems of access to care in particular. But while we have succeeded in containing the spread of the virus and treating the sick well, the economic, socialand even political situation is far from being under control. On the contrary, the epidemic has only weakened the already fragile economic health of the country after the health crisis linked to the plague epidemic in 2017.

Partial containment lasted one month in two of Madagascar’s main cities, Antananarivo and Toamasina. While people followed the instructions to the letter during the first two weeks, demonstrations then began in both cities. They were linked to the distribution of state aid and the ban on movement. Many people who work in the informal sector such as street vendors, rickshaw shooters, neighbourhood mechanics and other workers are not included in the social emergency plan announced by the government. The same is true for the self-employed, including temporary teachers, garage owners, farmers. This list is not exhaustive. Informal sectors of activity are hard hit by the measures of health restrictions. Households suffer from the loss of income. For businesses that have had to close down, the problem is different and more serious with human resources management, bank deadlines, rent etc.

At the political level, the bond of trust does not exist between the leaders and the people. The Head of State has constantly called on the people to trust the government in the strategies adopted to deal with the crisis during his television interventions. This only exacerbates tensions. Even the new societal order, called the Loharano Committee, which the government wanted to install at the neighbourhood level has not had the desired effect, even though it is planned that any organisation or proposal should start from this base and be passed on to the top. The committee only added to the tasks already assigned to the Fokontany, the first administrative level in Madagascar. Unsurprisingly, we have seen the intensification of insecurity, more and more armed attacks, burglaries in several neighbourhoods and even the return of kidnapping, which was almost non-existent during the first quarter of this year. But also the amplification of trafficking in protected animals and the exploitation of protected areas.

How is this crisis affecting the work of journalists?

Since the beginning of the crisis in China, “fake news” have been flooding the web. People are disoriented. They are not sure what to believe, which media or citizens to trust, especially on Facebook. This social network is becoming a machine for spreading “information” in bulk (videos – photos – rumours – misinformation) at full speed. Many people tend to give credibility to these kinds of publications because, it is said, they show what the media do not cover in their edition.

In fact, journalists want to respond to people’s information needs and concerns, but in times of crisis, freedom of information is affected by restrictions. The Malagasy government, for example, has limited the number of people who can intervene on the Covid to members of the Covid19 operational command centre, known as CCO-Covid-19. Most of its members are professors and medical specialists or law-enforcement generals. They attend meetings all the time, prepare their responses or are on the ground. As a result, they are rarely available to answer questions from the media. And sources outside the official circle rarely agree to give explanations for fear of being accused of “disturbing public order”. In addition, the service for the fight against cybercrime is stepping up repressive actions against the authors or peddlers of rumours, defamation and false information on Facebook.

The bipolarity of the media, similar to periods of propaganda, is more visible than ever, because of their affiliation to politicians who are opponents or close to power. The sources of information are not diversified, the word is given to a very restricted circle. This exposes young people and the population to misinformation and even manipulation.

How have you organized your newsroom, which is made up of very young journalists, to continue working in spite of the confinement? What are the main difficulties you have to overcome?

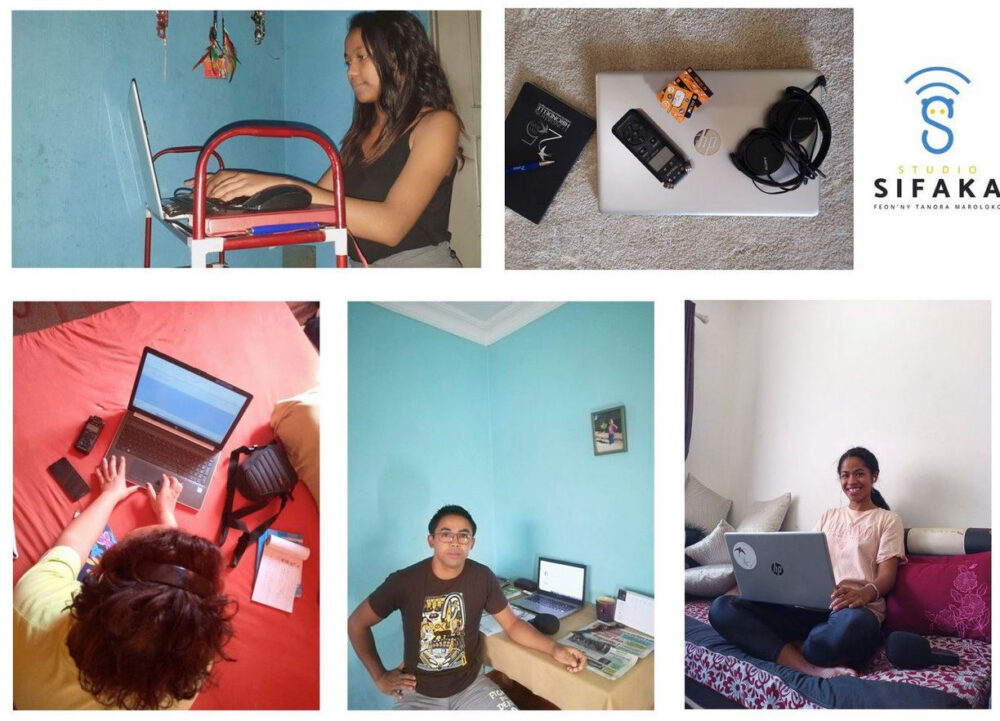

After the announcement of the partial confinement for the capital, we decided to telework even though it is a real challenge, both technically and organisationally. The protection of journalists – as human resources – is essential. We have to make the teleworking process work to ensure a one-hour daily programme for listeners. In times of crisis, radio plays an important role in educating, popularizing, and providing reliable and credible information. We have therefore informed our journalists of the decision to respect the containment while ensuring the work on a regular basis.

During the first two weeks of the lockdown, the editorial adviser, the director of the radio station, the editor-in-chief and the deputy editor-in-chief, assisted by Fondation Hirondelle’s editorial manager, handled the news bulletins and daily chronicles. Our two hosts were called in to ensure the presentation and the animation part. With two daily meetings at the beginning and end of the day for coordination and preparation. We organized the journalists into 5 distance working groups. They were mobilized to do news monitoring, to publish news on social networks and write articles for the website.

From the second half of the lockdown, we integrated the managers of each working group in the preparation of the programme. At the beginning we were afraid we would run out of topics… But this was not the case. Our young journalists surprise us every day. Some have even improved. We have become closer by calling each other often and have more time to talk in detail about each other’s angles and shortcomings.

The big difficulty is the internet connection. The speed of the connection changes from one neighbourhood to another and from one operator to another. We use a 4G mobile network type connection but there is always someone among us who experiences a slowdown in the connection when sending the edited material. There are also power outages in some areas.

It’s also harder for us to find speakers. Most of them don’t want to comment on official government information. Of course, we regularly take up some of this official information, but we want to focus on the angles that are also of interest to our audience. The opinions of experts, witnesses, entrepreneurs or connoisseurs are welcome, but often they are withdrawn at the last moment, even after having set up an appointment. Managing the replacement of one subject by another is a real headache, but we adapt.

What role can an information programme for young people like Studio Sifaka’s play in the face of such a crisis?

Studio Sifaka is a youth media that works to promote peace, a mission that is more relevant than ever since the arrival of this pandemic. Young people are very affected by the spread of Covid-19 and the measures applied in the country. Schools and universities have been closed, a number of activities have been suspended and traffic has been restricted. As a result, they have a very blurred vision of their future and are seeking more information to help them make decisions and see more clearly. Inviting them to speak allows them to express their feelings and concerns, even if it is a little difficult to put them at ease.

Studio Sifaka’s programme is not only focused on current news, but also includes musical entertainment and educational and entertaining programs. Soon, we will be introducing more cultural content to balance the programme offered to our young listeners: stories, sketches, radio drama and contests that will showcase their talents.