Philip Bennett, professor of journalism and public policy at Duke University and former managing editor of the Washington Post (2005-2009), analyzes the latest evolutions in the relationship between media and power. An interview for the latest Fondation Hirondelle’s quarterly newsletter, focused on “Governments and the media”:

Today, many governments show public mistrust towards traditional media. How do you situate this moment in the history of the relationship between media and power ?

Philip Bennett: The phenomenon you mention is indeed global: it is happening today in China, in Russia, in Turkey, but also in the United States under the Donald Trump administration of course, and to a lesser extent in France. It is linked up with the fact that the Internet provides the means for those in power to communicate directly with the public, without the intermediation of journalists. Political leaders have always tried to use new technologies to shape reality and deliver unfiltered messages to the public. Think of the use of radio in the 1930s and 40s by national leaders like Hitler, Churchill or Franklin Roosevelt. What is new today is that social media allows targeting messages to specific audiences, and for those audiences to communicate with each other. It also allows for greater control of information. When the Internet arose as a mass media in the 2000s, there was a great hope of increasing freedom of information and knowledge: anyone could have access to information on the Net, to discover new facts and find the truth. But in the 2010s, the Internet also appeared as a tool to spread false information and to control opinion. In the US, the power of social networks was harnessed by former US President Barack Obama, who had a very efficient use of new information technologies and the direct communication they allow to the public. In a very different style, Donald Trump’s has the habit of tweeting to attack enemies, challenge facts and announce new policies in 140 characters – a powerful way to prevent any public debate on his decisions.

I’d also say that there is an increasing trend in some democratic countries for governments to try to interfere in the media’s work, to spread the idea that media cannot be trusted, and to implement strategies to erode public trust in traditional media. Trump’s near constant attacks on the media are an obvious example. And, in more subtle ways, the Obama administration applied pressure on the news media through aggressive leak investigations. The Obama administration charged more people under the Espionage Act for leaking information to the news media than all previous US administrations combined.

What is new in democratic countries,

is that governments implement strategies to erode

public trust towards traditional media

Can traditional media resist this attack by governments?

There’s no doubt they should try. This is one of the defining contests in democracy today: do we have a public check of political power through media or are we losing that vital tool? That is a crucial issue. Democracy depends on the free flow of credible information to enable voters to make informed decisions. In the past months, US traditional media – mostly the Washington Post and the New York Times – have done an excellent job investigating Donald Trump’s campaign and his performance as president. They’ve published various stories that could have seriously jeopardized any president in the 20th century. But the Trump administration has benefited so far at least from widespread distrust of the news media, particularly among his supporters. Recent polls show only about 20% of Americans have a great deal of trust in the news media.

Speaking more broadly, I think we’re witnessing a global information war between various competitors – governments, corporations, NGOs, different kinds of opinion leaders. The traditional media is part of this contest, but no longer dominates the field. What is at stake in this war is public trust for democratic institutions, support for fact-based decision making and the rule of law. In this context, “fake news” has already won over some audiences, with the encouragement and backing of governments and others in power. The best weapons of traditional media in this war are an array of principles designed to make sure that they do serve the public interest – and not any private or political interest. Those principles are mainly based on: maintaining transparency, preventing conflicts of interest, and keeping separate facts and opinions. These principles were fairly widespread among US and European media a couple of decades ago. They have come under increasing pressure more recently.

In this information war, the best weapons of traditional media

are an array of principles designed

to make sure that they do serve the public interest

In the era of fake news spread through social networks, does the Washington Post Standards and Ethics, designed at the end of the 20th century, remain efficient enough to make the audience trust that traditional media serve the public interest?

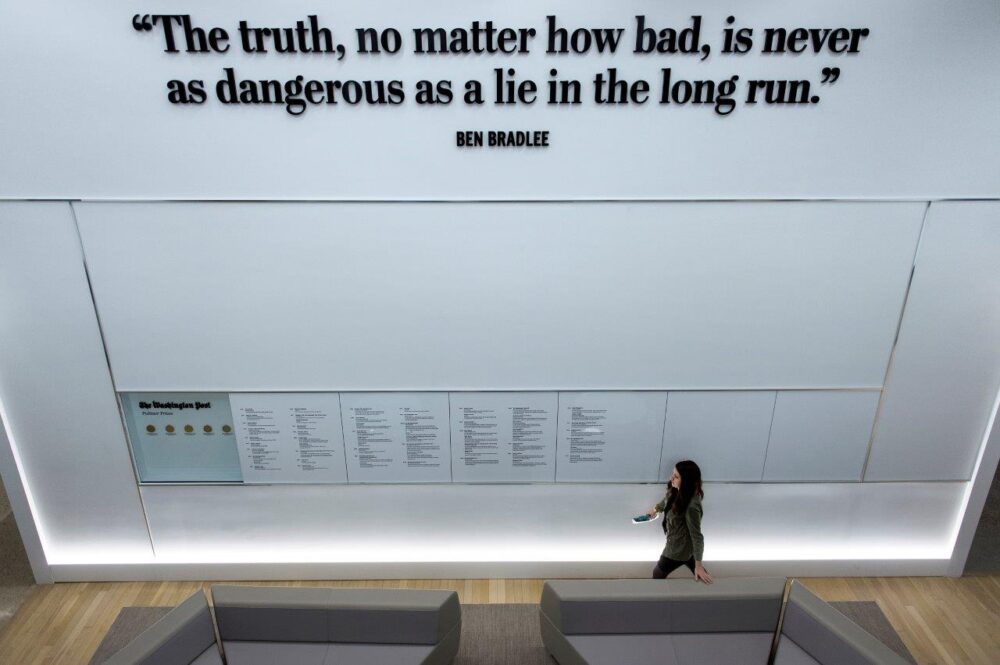

The Washington Post Standards and Ethics still have some relevance. They were designed not to restrain journalists, but on the contrary to increase their freedom and initiative, to make them investigate as widely as possible, without fear or favoritism. Nonetheless these principles, last updated in 1999, need constant renewal due to the fast evolution of media and information technologies. These principles have been completed in 2011 by Digital Publishing Guidelines to ‘maintain credibility’ of The Post’s journalists on social networks. Indeed, one has to consider that a main mission of the media is still to hold power accountable. The best way to do so, in my view, is not to become an opposition media, trying to advocate for one side or another, but to remain a disinterested media trying to reveal the facts and discover the truth of a situation. Not to oppose the government, but to try to publish what the government does in private or in secret, true stories that the public needs to know and the government wants to keep from the public. And you can be such a media only if you maintain your independence.

Interview by Benjamin Bibas / la fabrique documentaire for Fondation Hirondelle.

This article is published in the Autumn issue of our newsletter “What’s new”, to be downloaded here.