In a world where social networks are a major source of information and disinformation, knowing how to distinguish a fact from a lie is a major democratic issue. The media need to play their role fully in this task of education, explains Caroline Vuillemin, General Director of Fondation Hirondelle, in an Opinion Column published on January 27, 2021 by the Swiss newspaper Le Courrier.

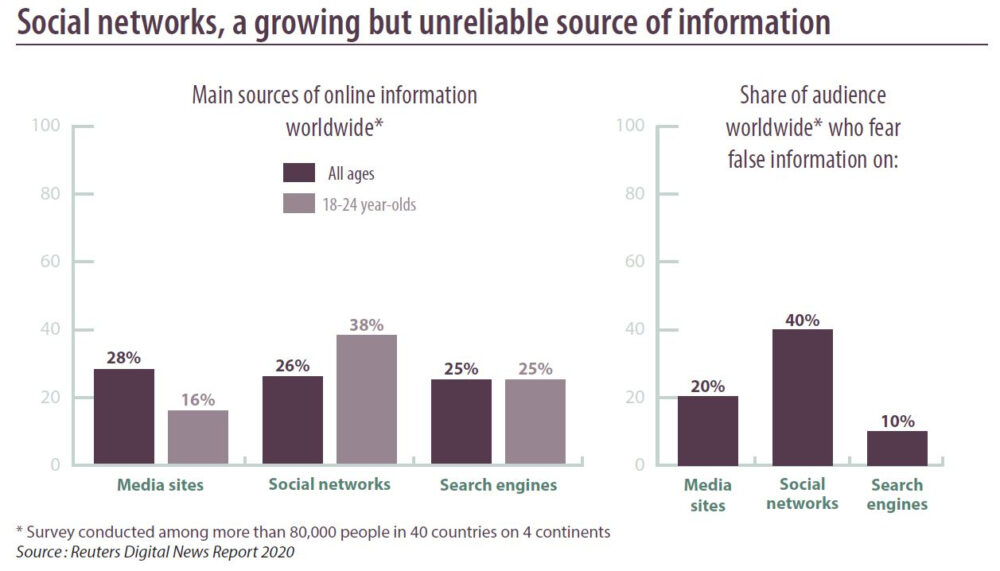

In 2020, social networks were the main source of news information for 26% of Internet users worldwide, almost equal to media sites (28%) and search engines (25%). This was especially true among young people: 38% of Internet users aged 18 to 24 look for news first on social networks. Yet four years after the Cambridge Analytica scandal – named after the British company that massively disseminated false information to targeted psychological profiles on social networks in order to influence their votes – little has been done to improve the reliability of the information shared there. Some 20 states have legislated against online misinformation, restricting the spectrum of messages that could be disseminated on social networks. But some of these laws are part of censorship measures implemented by authoritarian regimes. For their part, social networks have begun to address this problem, which is damaging their reputation, but much remains to be done to help the public find reliable information online.

For about twenty years, there has been an international framework within UNESCO to do this: Media and Information Literacy (MIL). This aims to improve the capacity of people to “receive and disseminate information in a relevant, ethical and critical manner”, in order to better implement their right to information recognized by Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Helping citizens of all ages and all categories to extricate themselves from the mire of more or less violent propaganda on the web has become a major global challenge. It does not only concern States, international organizations, schools and universities, but also the media themselves.

To ensure that the information they process and publish can continue to be seen, heard, read and believed by as many people as possible, the media are now obliged to explain more about how they work. The mission of journalism is not to educate, but to inform. Processing and providing clear, accurate information is not the same as teaching people to read, write, and count. These two missions, both as necessary as each other, each require specific skills and qualities. Journalists as teachers can, however, contribute to the same general interest objective: to help us understand how the world works.

Given the disinformation that floods social networks and a tendency to put opinions and facts on the same level, those whose profession is to present reality as it is must now, in order to be credible, explain how they work. Showing and helping people understand the techniques and principles that guide the production of information is one of the objectives of “media education”. It is also explaining how to distinguish information, factual and verified, from a lie or an attempt at manipulation. The role of journalism is also to put assertions to the test. Fondation Hirondelle has been doing this for 25 years, with its journalists, media and partners in contexts where credible information can sometimes save lives. From Mali to Myanmar, from Niger to Bangladesh, from Burkina Faso to Madagascar, via the Central African Republic, in these countries among the most fragile in the world, access to reliable information is a basic necessity. This need for quality information is more vital than ever, over there as here, against alll forms of disinformation and new digital divides.