A new amnesty law for Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) fighters has been before the Ugandan parliament has since 2015. It would put an end to the existing ambiguity between the general amnesty law of 2000, which is currently in force, and Uganda’s International Crimes Chamber. But the debate has not yet been settled: is it better to amnesty the perpetrators of terrible crimes in the name of peace, or prosecute them under criminal law in the hope of advancing reconciliation? A paper by Pierre Hazan, associate professor at Neuchâtel University and Editorial Advisor for JusticeInfo.net, Fondation Hirondelle’s website on justice and reconciliation processes around the world.

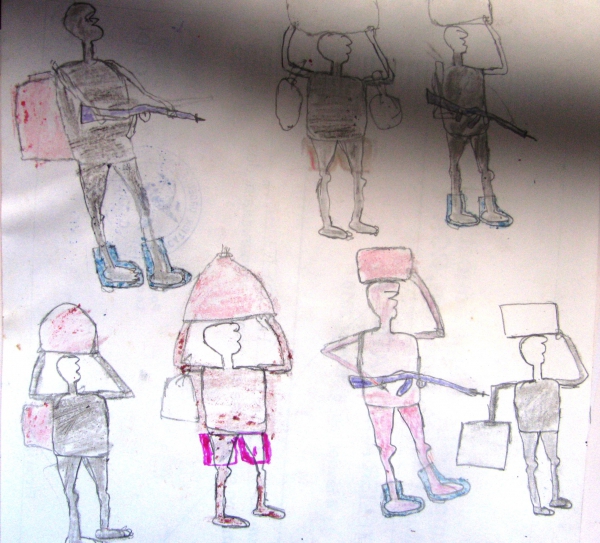

This is a deep dilemma. Since 1986, the LRA has kidnapped tens of thousands of boys and girls. It has turned them into pitiless child soldiers, drugged them and made them into killer robots and sex slaves. To weaken the LRA, the Ugandan government adopted a general amnesty law in 2000. The second section of the amnesty law says:

“An amnesty is declared in respect of any Ugandan who at any time since the 26th day of January, 1986, engaged in or was engaging in war or armed rebellion against the Government of the Republic of Uganda by: actual participation in combat; collaborating with the perpetrators of the war or armed rebellion; committing any other crime in the furtherance of the war or armed rebellion; or assisting or aiding the conduct or prosecution of the war or armed rebellion [and who renounces and abandons war.]”

International law

This law sparked an international outcry. It was denounced by the office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights as a violation of international law. In addition, the Ugandan government has ratified the Statutes of the International Criminal Court, integrating them into domestic law in 2010, but the ICC Statutes outlaw amnesties for perpetrators of international crimes (genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity). The ICC is currently trying Dominic Ongwen, one of the five LRA leaders indicted by the Court in The Hague. Ongwen, who was himself kidnapped by the LRA before becoming one of its leaders, faces 70 charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

So should the general amnesty law of 2000 be scrapped, as urged by the ICC? This law also limits rights to truth and reparations for victims of the LRA. It thus favours perpetrators at the expense of victims, as denounced by the NGO REDRESS, which stresses that the amnesty law is linked to a Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) process for combatants. The terrible ironic consequence is that the kidnapped children, especially girls forced into LRA marriages, were excluded from this law whilst the perpetrators were granted not only an amnesty but an “aggression bonus” in the shape of a small sum for reintegration. This discrimination against victims is not conducive to reconciliation.

Hence the Ugandan government’s idea of making the amnesty law more restrictive, with no amnesty for perpetrators of international crimes. This would bring Ugandan law into line with the ICC. Another factor in favour of more restrictive amnesty provisions is that the security situation has considerably improved, as there have been no LRA acts of violence inside Uganda since 2006. This new amnesty law would also end the confusion that has prevailed since the International Crimes Division, a special chamber of the Ugandan High Court, was created in 2008. This Chamber is trying Colonel Thomas Kwoyelo of the LRA, who is accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity. But at the same time, one of his superiors, Caesar Acellam, got amnesty under the 2000 law, reflecting the fact of selective justice.

Parliamentary dilemma

Nevertheless, MPs are dragging their feet over the adoption of this new law, for good reason. The 2000 amnesty law has brought some good results: 27,000 LRA fighters have, it seems, benefitted from it (half as many, according to official statistics), which is an impressive figure. The proponents of amnesty also say that the judicial approach is not suited to LRA fighters, because many of the perpetrators are also victims, as stressed by Kasper Agger of the “Enough Project”. “Horrible crimes are indeed committed by the LRA, but the fact remains that the vast majority of the rebels are forcefully abducted, some at a very young age, and forced to commit the crimes,” he says. “Thus a strict distinction between victim and perpetrator does not exist, hence limiting the ability of the legal system to deal with LRA crimes”. And another argument put forward by those in favour of amnesty is that nobody from the Ugandan army has ever been prosecuted, despite allegations by many Ugandan and international organizations of serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law. Last, but not least, as SOAS professor Phil Clark explained to the IRIN news agency, “the changes to the Amnesty Act may dissuade middle- and high-ranking rebel leaders from returning. They may believe they fall within the new exceptions to the amnesty and may believe it is preferable to continue fighting rather than surrendering and risking prosecution in Uganda”.

How best to reconcile the need for justice and reconciliation and the need for stability? Can there be peace without justice? Is justice possible and, if so, what kind of justice? In Uganda, these questions remain as yet unanswered.

Pierre Hazan, JusticeInfo editorial advisor and associate professor at Neuchâtel University